What Are the Parts of the Stomach?

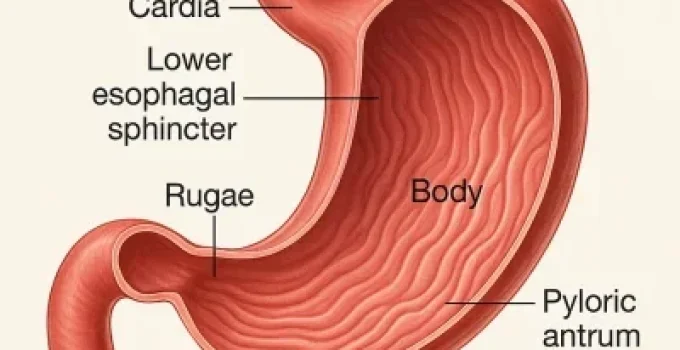

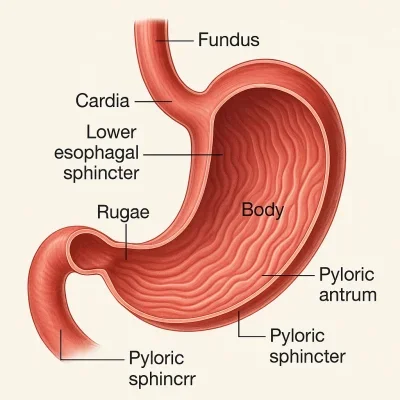

The human stomach is divided into four main anatomical regions: the cardia, fundus, body, and pylorus. Each of these parts plays a unique role in the process of digestion—from food entry and storage to mechanical churning and chemical breakdown. These regions are further supported by two important sphincters, as well as internal gastric folds (rugae) and a multi-layered wall that enables the stomach to function as a dynamic, muscular organ.

Dive Deeper

- Overview of Stomach Regions

- Important Sphincters

- Internal Features: Rugae and Glands

- 🧩 Stomach Region Comparison Table

- 🎯 Final Thoughts

- 📚 References

Overview of Stomach Regions

Anatomically, the stomach can be described as a J-shaped organ composed of specialized sections. Each part plays a structural and functional role in digestion:

- Cardia – entrance from the esophagus

- Fundus – the upper dome, gas reservoir

- Body (Corpus) – main digestive region

- Pylorus – prepares food for small intestine transfer

Two curvatures outline the stomach:

- Lesser curvature (medial, inside curve)

- Greater curvature (lateral, outside curve)

1. The Cardia

Located just beneath the esophagus, the cardia is the first part of the stomach. It contains the cardiac sphincter (lower esophageal sphincter), which:

- Allows food to enter from the esophagus

- Prevents acid reflux by closing after swallowing

🔍 Though small in size, the cardia plays a vital role in regulating flow between the esophagus and the stomach [1].

2. The Fundus

The fundus is the rounded, upper portion of the stomach that extends above the esophageal entry point.

- Acts as a gas storage area (from swallowed air or fermentation)

- Lies under the diaphragm, helping in gentle expansion during a meal

- Participates minimally in digestion but assists in storage

3. The Body (Corpus)

The body, or corpus, is the largest part of the stomach and the main site of digestion. It is responsible for:

- Churning food through muscular contractions

- Mixing with gastric juices (hydrochloric acid and enzymes)

- Breaking down proteins via the enzyme pepsin

This region contains most of the gastric glands, including chief cells and parietal cells.

📊 The body of the stomach typically holds 60–80% of total gastric volume during digestion [2].

4. The Pylorus

The pylorus connects the stomach to the duodenum (first part of the small intestine) and has two subregions:

- Pyloric antrum – grinds and liquefies food

- Pyloric canal – leads to the pyloric sphincter, controlling emptying into the duodenum

This region plays a key role in regulating gastric emptying, allowing only small amounts of chyme to pass through.

Important Sphincters

| Sphincter | Location | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Lower Esophageal (Cardiac) | Between esophagus and cardia | Prevents backflow of acid (reflux) |

| Pyloric Sphincter | Between pylorus and duodenum | Controls release of chyme into the intestine |

These muscular valves ensure one-way movement of food and maintain compartmentalization within the GI tract.

Internal Features: Rugae and Glands

Rugae (Gastric Folds)

- Allow the stomach to expand after meals

- Help with gripping and mixing food during digestion

Gastric Glands

Located in the mucosa layer, these glands include:

- Chief cells – secrete pepsinogen

- Parietal cells – secrete hydrochloric acid (HCl) and intrinsic factor

- Mucous cells – produce protective mucus

🔬 The gastric lining renews itself every 3 to 5 days to prevent damage from harsh acids [3].

🧩 Stomach Region Comparison Table

| Region | Location | Main Function |

|---|---|---|

| Cardia | Just below the esophagus | Food entry; prevents acid reflux |

| Fundus | Upper dome, near diaphragm | Gas storage; expansion |

| Body | Central, largest section | Churning, digestion, acid secretion |

| Pylorus | Lower, near small intestine | Grinding food; regulates exit |

| Rugae | Inner folds of mucosa | Expansion; surface area for secretion |

| Sphincters | At entry and exit points | One-way flow control |

🎯 Final Thoughts

The stomach is more than just a simple container for food—it’s a carefully structured organ, with distinct regions that perform specialized tasks. From the cardia’s gateway role to the pylorus’s precision release, each part contributes to the stomach’s ability to receive, store, break down, and deliver food to the small intestine in a highly controlled process.

By understanding the anatomy of the stomach’s parts, we gain deeper insight into how digestion begins—not just chemically, but structurally.

📚 References

- Drake, R.L., Vogl, A.W., & Mitchell, A.W.M. (2020). Gray’s Anatomy for Students (4th ed.). Elsevier.

- Guyton, A.C., & Hall, J.E. (2016). Textbook of Medical Physiology (13th ed.). Elsevier.

- Tortora, G.J., & Derrickson, B. (2017). Principles of Anatomy and Physiology. Wiley.

- NIDDK. “Your Digestive System & How It Works.” https://www.niddk.nih.gov